‘Mind Reading’ is Possible: Scientists Successfully Sent Thoughts Over The

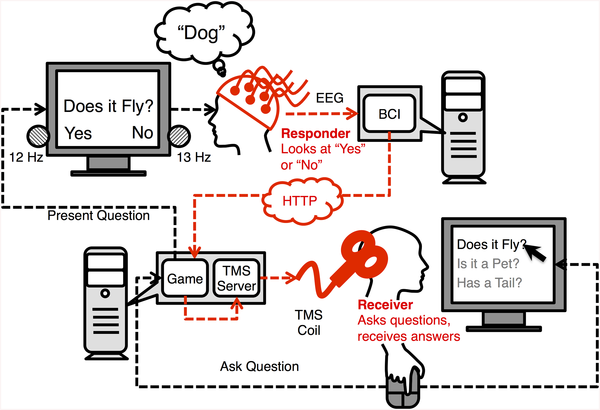

University of Washington postdoctoral student Caitlin Hudac wears a cap that uses transcranial magnetic stimulation (TMG) to deliver brain signals from the other guessing-game participant. In the study, participants were able to guess what is in another person’s mind regardless that they are a mile apart. Researchers at the University of Washington have figured out a way to connect the brains of two people via the Internet and play a game of “20 questions” without even speaking.

This is the most complex brain-to-brain experiment, I think, that’s been done to date in humans. The light for “yes” flashes at a different frequency than the light for “no”.

One participant had to wear a cap connected to an electroencephalography (EEG) machine, which records electrical brain activity, while the other sat in a lab nearly a mile away.

The respondent was given an object on a screen to focus on, while the inquirer was given with a list of possible objects and a list of “yes” or “no” questions.

The second subject, who is called the “inquirer”, views several objects and its related questions.

To answer, the respondent looked at either the word “yes” or “no” on his screen. After some period of concentration, a brainwave signal would be transmitted back to the original participant through a magnetic coil.

“They have to interpret something they’re seeing with their brains”, said co-author Chantel Prat, a faculty member at the Institute for Learning and Brain Sciences and an associate professor of psychology.

Stocco said the success of the experiment took researchers by surprise. In the real games, players guessed the correct object 72 percent of the time, compared to just 18 percent of the control rounds. Possibilities being explored include transferring knowledge directly from a teacher’s brain to a student’s brain. And the team believes many of those incorrect guesses were caused by the inquirers not being able to recognise the phosphene, or visual hallucination, that signalled a “yes” response. A “yes” sent a signal to the questioner; a “no” sent no signal at all.

To indicate his or her answer, the respondent directed his or her gaze to either of two LED lights, one flashing at 13 Hz coding for “yes”, the other flashing at 12 Hz for “no”. Two years ago, Stocco and computer science professor Rajesh Rao conducted an experiment in which Rao transmitted signals from his brain to Stocco, causing his finger to twitch.

The team hopes that their experiment could lead to game-changing applications including data transfer from one person to another or the transmission of the brain state from an alert individual to an exhausted one.

Many technological advancements over the past century, from the telegraph to the Internet, were created to facilitate communication between people.

“We can only communicate part of whatever our brain processes”, Stocco said.

“But it requires a translation”. Of course, that is the stuff of dreams and science-fiction flicks: in the real world, the closest that scientists have come to establishing direct communication between brains involves an extremely convoluted apparatus and would take hours to transmit the amount of information you typically exchange in a 2-minute conversation.