Venus Transit Captured Phenomenally, Provides Opportunity for Scientific

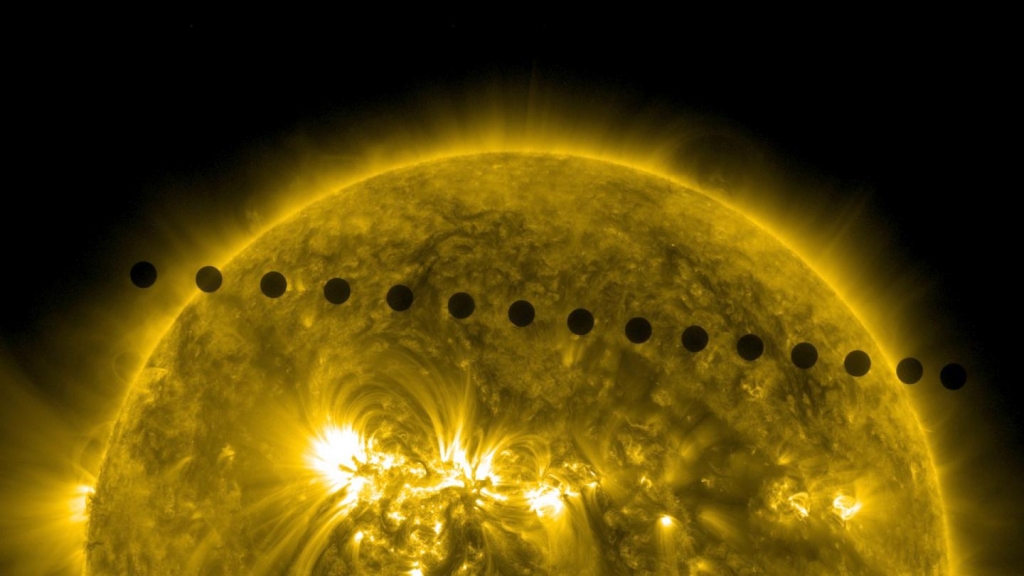

It happens just twice every 115 years, with 8 years between transits. In an attention-seeking plot, the planet lit its atmosphere in the rays of the sun, forcing the eyes of the Solar Dynamics Observatory of NASA, upon it. This may seem like a pretty common event.

Venus transit, an extremely rare event in which a planet passes between the Earth and sun, can now be used to make measurements about the way in which the atmosphere of Venus absorbs different kinds of light.

The previous transit occurred in June 2004.

Reale and his team chose images of the Venus transit taken in several X-ray and ultraviolet wavelengths and measured the apparent size of the planet to within several miles.

The high resolution of the images, combined with the sun providing backlighting, allowed a team of researchers to learn about the composition of Venus’ atmosphere. Venus’s atmosphere is layered, just like that of Mars, or Earth. For instance, some layers may absorb a certain wavelength of light completely, which another might not absorb it at all. Now, by studying images of the backlit planet crossing our sun, astronomer Fabio Reale and his colleagues at the University of Palermo have worked out what sorts of molecules and atoms are present in Venus’s atmosphere. They will have a better insight into how the universe works and gain an even better understanding of the differences and similarities between planets of varying sizes, atmospheres, and distances from each other. These new pictures will help researchers and scientists study the planet, its atmosphere, and how various elements of the planet react and change to the sunlight.

Because the various types of atoms absorb light slightly differently, the height of this light absorption lets scientists know how many and what types of molecules make up Venus’s atmosphere. In the ionosphere, a layer created by radiation being absorbed by the atmosphere and creating ions that capture light. They concluded that the atmosphere of the planet does not undergo changes when sun sets, or when it rises. The wavelength is 171 angstroms.

Venus’s transit may be stunning, but it’s paving the way toward what could be the most important scientific discovery of the century.

This information’s is useful to any future missions to Venus as well as identifying similar planets as they cross in front of distant stars. On Earth, these transition areas can host interesting effects in the ionosphere, the data from the Venus transit showed that these two transition areas have virtually nothing distinct from one another.

“The planet appeared very round in all wavelengths”, said Pesnell.

This bulge never eventuated, which means the atmosphere remains the same at sunrise and sunset.

Future missions, beginning with the James Webb Space Telescope in 2018, will have the powerful optics needed to catch the light filtered through the air of distant worlds.

The next time Venus is due to pass between the Earth and the sun will be in December 2117.