Ada Lovelace’s letters and work on display at Oxford library

Ashfield MP Gloria De Piero recently visited the Ada Lovelace building in Kirkby.

Ada Lovelace was a pioneering mathematician, the first female computer programmer and the daughter of Lord Byron, whose ancestral home was at Newstead Abbey.

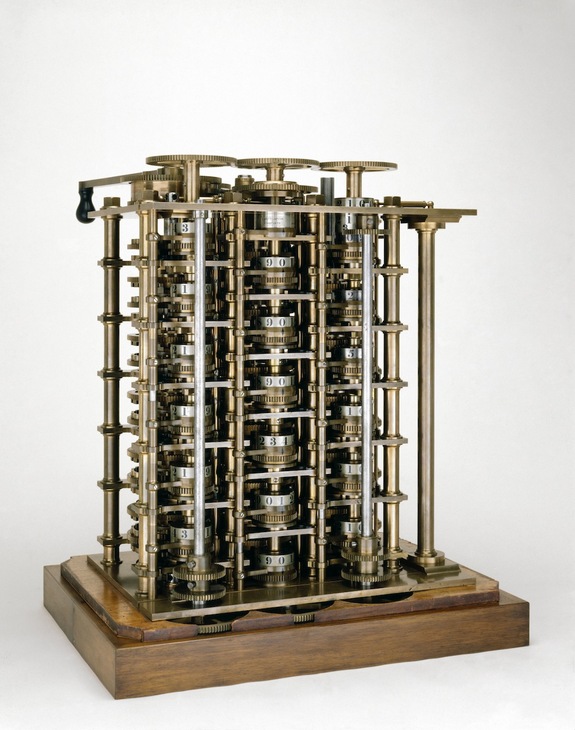

“This was a machine that could use numbers, not just to represent quantities, but also as abstract values, and it marks the prehistory of the computer age”, said the museum. This becomes even more impressive when you realise that she wrote the first ever line of code in 1842.

While the medical and scientific communities would still kill for such a model today, Lovelace’s interest in the inner-workings of complex machinery led her eventually to Babbage and his, at the time, unmade Analytical Engine.

Ada, Countess of Lovelace, was born in 1815 and was the only legitimate daughter of poet Lord Byron. The event is about sharing inspiring stories of women in science, to create role models for girls and women who may be unsure about entering such a male-dominated field. Those notes she compiled totaled three times the length of the inventor’s own, entitled “Sketch of the Analytical Engine, with Notes from the Translator”. Lovelace’s reports on the machine included early computer programs, which were the first to be published.

She excelled at the subject, with Babbage describing her as “The Enchantress of Numbers”.

Though the “analytical engine” and its punchcard mechanical system were never built in the 19 century, the Lovelace writings would apparently inspire Alan Turing and his computational breakthroughs more than a century later. Dying at the young age of 36, it was a life few could match in twice as many years, and one that should be far more widely recognised than it is today.

Women are sometimes considered outsiders in the science and technology fields, but Lovelace and numerous female computer programmers who followed her are proof that this paucity is a function of society, not capability.