Trial of Hissene Habre Begins

Habre, who ruled in Chad from 1982-1990, is facing charges of crimes against humanity, war crimes and torture before the Extraordinary African Chambers, a special tribunal created to try him in the Senegalese courts.

Once dubbed “Africa’s Pinochet”, the 72-year-old has been in custody in Senegal since his arrest in June 2013 at the home he shared in an affluent suburb of Dakar with his wife and children.

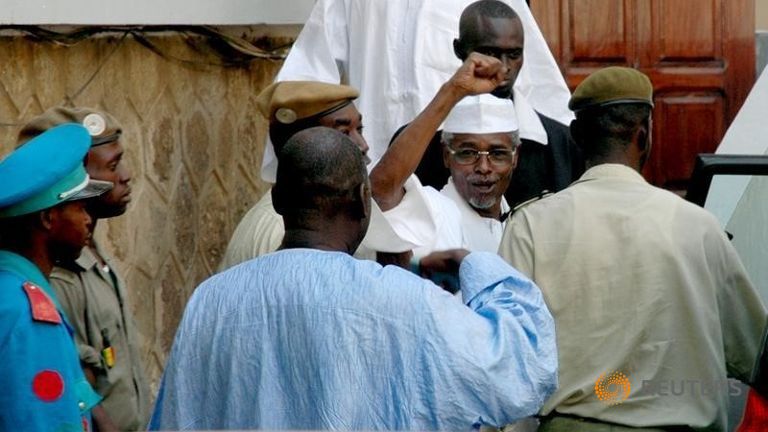

Dressed in white robes and a turban, Habre pumped a fist in the air and cried “God is greatest” as he was escorted by prison guards into the Extraordinary African Chambers in the Senegalese capital.

The courthouse, packed with around 1,000 participants, spectators and local and global media, heard a number of introductory speeches before it emerged The defendant was refusing to enter the dock.

Several supporters, mostly young, screamed slogans and scuffled with police as they too were removed.

Former Chadian President Hissene Habre is going on trial in Senegal for alleged human rights crimes, including 40,000 murders.

He was overthrown by rebel troops in December 1990 and fled to Senegal.

The trial of Habre will be closely followed by his victims, Abaifouta said.

“We must have the capacity to try our own leaders right here in Africa”.

The hearings will set a historic precedent as until now African leaders accused of atrocities have been tried in worldwide courts.

The trial marks the end of a 15-year battle to bring him to justice in Senegal, where he has lived in exile after being toppled in a coup.

Macky Sall, Wade’s successor who took office in April 2012 vowed to organise a trial in Senegal.

It is the first trial in Africa of a universal jurisdiction case, in which a country’s national courts can prosecute serious crimes committed overseas, by a foreigner and against foreign victims, said Human Rights Watch.

“So there are a lot of historical aspects to this”, he said.

Souleymane Guengueng, a former accountant who spent more than two years in Habre’s prisons, is among some 100 victims due to testify at the trial.

“It shows that you can actually achieve justice here in Africa”, said Human Rights Watch counsel Reed Brody who has been working on the case against Habre since 1999.

The ICC was embraced by many African governments when it was set up in 2002, but attitudes towards the largely European-funded court have cooled after it has indicted only Africans, prompting many to label it a Western-controlled, neo-colonial institution.

United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights Zeid Ra’ad Al Hussein described the opening of the trial as a “milestone for justice in Africa”.

The case against Habre turns on whether he personally ordered the killing and torture of political opponents and ethnic rivals.

“The court president’s decision to bring Habre by force tomorrow is a relief to the victims who want to look him in the eyes and ask why they were jailed and tortured, why their loved ones were killed”, he added.