Human DNA tied mostly to single exodus from Africa long ago

We know that the ancient humans and Neanderthals – a human cousin that had already successfully taken hold outside of Africa – were getting it on regularly somewhere around 65,000 years ago, possibly even as much as 100,000 years ago.

We still don’t know the exact timing of that migration, precisely where it began, nor the details of movements and how individual populations developed within Africa. When exactly did we first leave the continent and was there just one exodus?

One of the curious findings of the paper: our ancestors, the population that led to every human on the planet, started to diversify into distinct groups 200,000 years ago or more. Later, they eventually spread north-east over the top of Beringia into the Americas.

Previous research unearthed bones from a mysterious extinct branch of the human family tree from Denisova cave in Siberia’s Altai Mountains.

Genetics has been invaluable in understanding this past.

The key to getting a clearer picture of what went down in our ancient history will now be to combine genetic evidence with archaeological evidence – something the three new studies didn’t fully explore.

The study also suggests that the KhoeSan (bushmen) and Mbuti (central African pygmies) populations appear to have split of from other early humans sooner than this, again suggesting that there was no intrinsic biological change that suddenly triggered human culture. If two genomes share long stretches with no differences, it’s likely that their common ancestor was in the more recent past than the ancestor of two genomes with shorter shared stretches. “The answer to that question is yes – our data is completely consistent with aboriginal Australians descending from the first humans to enter Australia”.

SGDP model of the relationships among diverse humans (select ancient samples are shown in red) that fits the data. Sidenote: Bubble of Hominins is an excellent name for a band. Credit: Swapan Mallick, Mark Lipson and David Reich.

The Simons Genome Diversity Project compared the genomes of 142 worldwide populations, including 20 from across Africa.

Genetic differences between Aboriginal populations were also exacerbated by the last ice age, which occurred about 20,000 to 30,000 years ago. This indicates that there was substantial substructure of populations in Africa prior to the wave of migration.

Aboriginal Australians and Papuans then diversified between 25,000 and 40,000 years ago, long before Australia and New Guinea separated in the early Holocene (about 11,500 years ago).

Following the move out of the continent, the pioneers must then have journeyed incredibly quickly to Australia. Some researchers have posited that the ancestors of the Aborigines were the first modern humans to surge out of Africa, spreading swiftly eastward along the coasts of southern Asia thousands of years before a second wave of migrants populated Eurasia.

Yet we had known for some time that groups of modern humans made forays outside their “homeland” before 60,000 years ago. “It’s nearly like two guys entering a village and saying ‘guys, now we have to speak another language and use another stone tool and they have a little bit of sex in that village and then they disappear again”.

“What that means is that there are very significant differences between the genomes of people in the east and the west”, David said. The Simons Genome Diversity Project study, by contrast, albeit with a far smaller sample of Sahulian genomes, found no evidence for such an early Sahulian split.

A graphic representation of the interaction between modern and archaic human lines, showing traces of an early out of Africa (xOoA) expansion within the genome of modern Sahul populations.

The researchers suggest that at least 2 percent of the Papuan genome harbors traces of an early migration that happened about 120,000 years ago. This migration is only visible in the genomes of a separate set of Sahulians sequenced as part of the Estonian Biocentre Human Genome Diversity Panel. They conclude that, if the genetic legacy of such a migration survives in these populations, it can’t comprise more than a few per cent of their genomes.

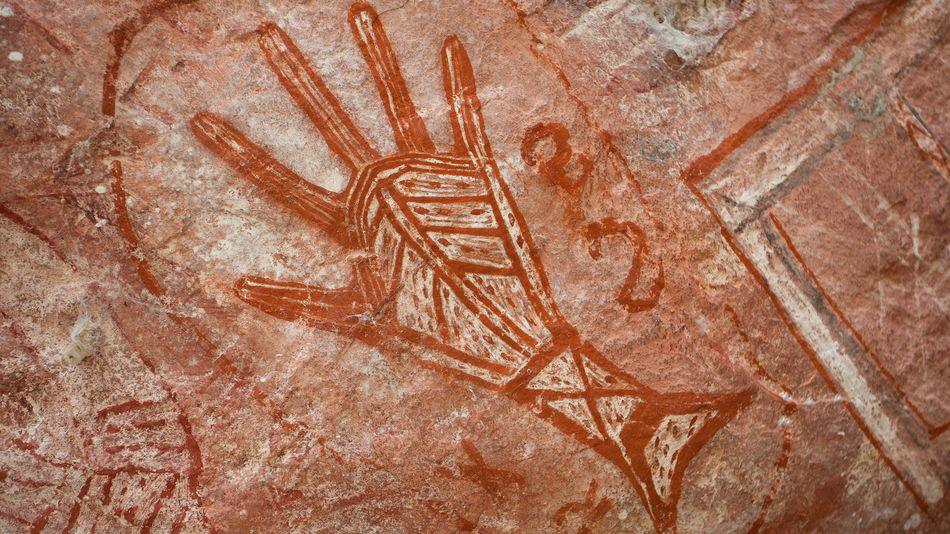

Australia’s single founding population gives it “one of the longest histories of continuous human occupation outside Africa”, according to the study, and Aboriginal Australians are linked to some of the earliest evidence of modern human behaviour. Read the original article.