There is no safe limit to alcohol consumption, study say

For people over 50, cancers were cited as a leading cause of alcohol-related death (about 27 percent of deaths in women and 19 percent of deaths in men).

Commenting on the problem-drinking patterns of older women, Dr Garrett McGovern, a Dublin addiction counsellor, said that, from his experience, a large proportion of them would drink at home in the evening. It’s even higher in Italy, Portugal and Spain.

Its findings show that in 2016, nearly 3m deaths globally were attributed to drinking alcohol, with 12pc of these deaths being males aged between 15 and 49.

Even moderate drinking can increase the risk of cancer and other diseases, according to the research released yesterday, which points to abstinence as the only safe course of action.

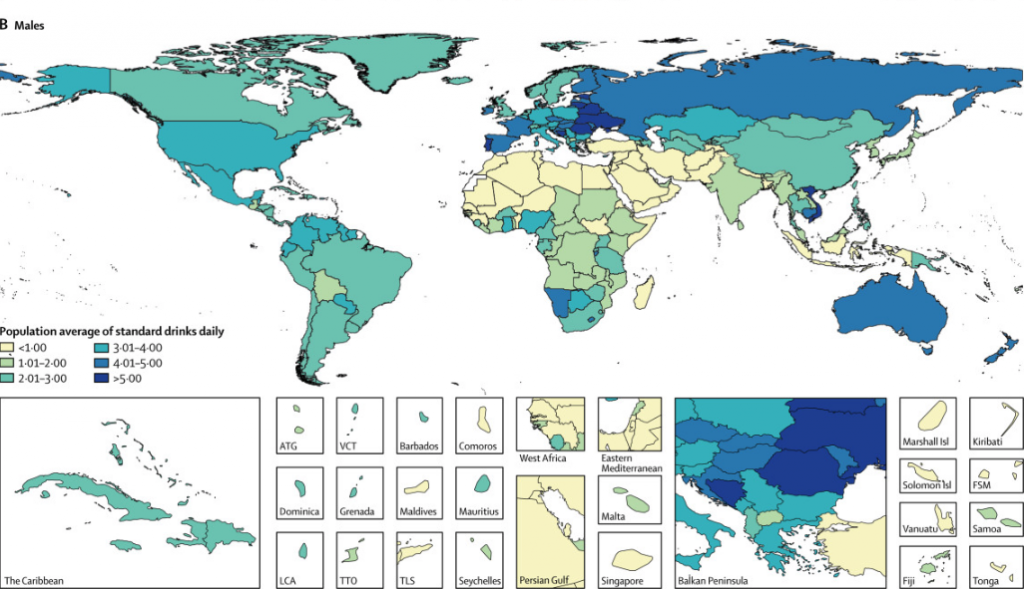

Researchers at the Institute of Health Metrics and Evaluation in Seattle looked at the effects of alcohol consumption on research participants aged between 15 and 95 in 195 countries from 1990 through 2016.

The researchers reviewed data from 694 studies to figure out how common drinking was around the world.

“There is a compelling and urgent need to overhaul policies to encourage either lowering people’s levels of alcohol consumption or abstaining entirely”.

These results aren’t comforting either: Any amount of alcohol use was linked to worsening health conditions, although, as expected, the risk was contingent upon how much a person drinks. Diageo has also acquired a minority stake in Seedlip, an alcohol-free drink that aims to deliver the depth of flavor and mouthfeel of a high-end spirit.

They found no evidence that light drinking might help keep people healthy and said there is no evidence that drinking any alcohol at all improves health. It was not among the top or bottom 10 for the most or the heaviest drinkers in 2016.

Every year 2.2.% of women and 6.8% of men die of alcohol-related health problems including cancer, tuberculosis, and liver disease.

The countries that drink the least alcohol have mostly Muslim populations.

But the new study found for every 100,000 people who consumed two drinks a day, there would be an extra 63 cases of ill health a year. That might be true in isolation, Gakidou said, but the picture changes when all risks are considered.

Any protection against heart disease, stroke and diabetes offered by alcohol turned out to be “not statistically significant”, said the researchers.

Although it claims in absolute terms that there is no safe level of drinking connected with alcohol, what it fails to acknowledge is that, actually, the risks of moderate drinking are in fact very low.

“Our findings are consistent with other recent research, which found clear and convincing correlations between drinking and premature death, cancer and cardiovascular problems”, said Dr Emmanuela Gakidou, senior author of the study.

But the new paper, published Thursday in The Lancet, calls that long-held conclusion into question. Majority relied on self-reported information, which means people have to remember their drinking habits accurately, which means the data might be flawed or inaccurate, according to CBS.