Federal Experts: Current El Niño Could Be Historically Strong

July was the hottest on record globally as a large El Nino event gathered strength in the Pacific, making it more likely that 2015 will exceed last year as the warmest year recorded.

Analysts say heavy rains may not compensate for four-year drought in California.

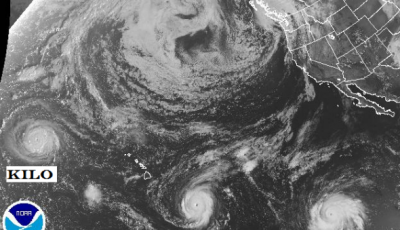

A weather forecast suggests the Pacific Ocean’s strengthening El Nino, warming the water, has the potential to be the strongest on record. But, just what is El Nino, and how might it affect the Carolinas?

NOAA in March declared the arrival of the El Nino, which is defined as warmer-than-average sea surface temperatures in the central Pacific Ocean near the equator (see Daily GPI, March 6). “As a result you tend to have less mountain snow pack, and after this past weather season with such a meager snow pack, that can be a problem for our water supply”. The state would need one-and-a-half times its normal rainfall to get to end the dry season…

In St. Louis the Meteorologist in Charge at the National Weather Service, Wes Browning agrees the El Nino that is forming is historic and he explains what it could mean for Missouri and the rest of the Midwest.

“It could mean about a 60 to 70 percent better chance for above normal precipitation along the west coast.” says Browning. The Climate Prediction Center researchers anticipate water temperatures could reach 3.5 degrees above normal in the region, which gave birth to the weather system.

Experts said El Nino was one of the factors which contributed to the so-called “Big Freeze” but there were others.

According to the most recent Drought Monitor from the National Drought Mitigation Center, most of Arizona, California, Idaho, Nevada, Oregon, Utah, Washington, and western Montana and New Mexico are now in moderate or exceptional drought.

Predicting an El Nino’s impact on the Reno-Tahoe area is hard because the region lies in a transition zone that can experience wet, dry or average winters when one is in place. But sometimes, the El Nino would last not a few months, but sometimes, six months or even more.

We only have reliable ENSO (El Nino Southern Oscillation) phase data back to the 1950s, so there is still much we don’t know.

In El Nino years, Pacific currents subside and sometimes change direction.