Britain approves controversial gene-editing technique

The research will see scientists cutting into the genetic code of embryos, isolating individual segments of DNA and assessing how they contribute to the early growth and behaviour of the embryos.

The committee has mentioned a condition in the license that research involving gene editing can not take place until the research has received research ethics approval.

“Whilst we note the HFEA restriction on the implantation of genetically modified embryos, it is sending the wrong signals by allowing scientists the ability to develop and possibly flawless the technology here in the UK”.

The genome editing technique is named Crispr/Cas9.

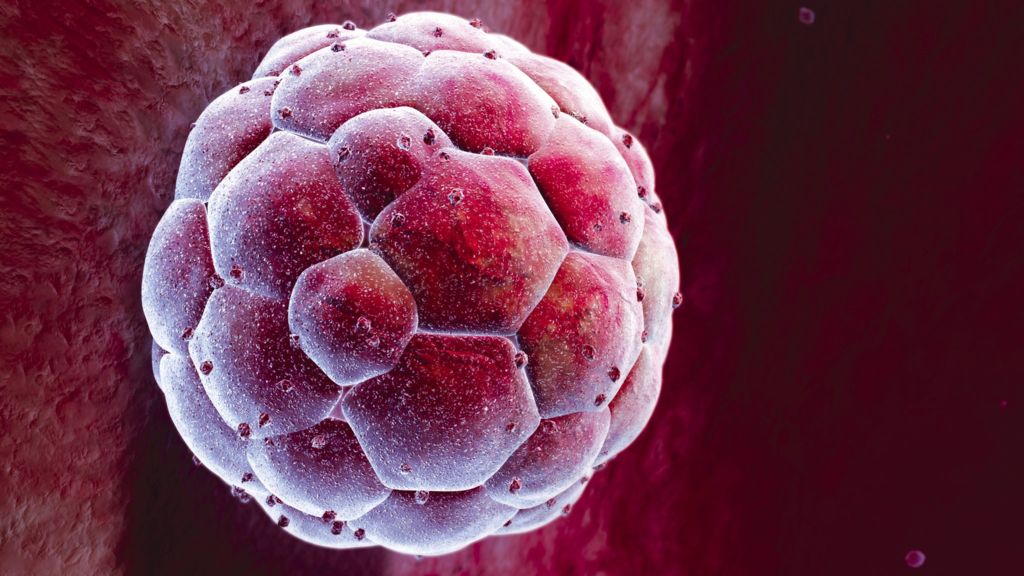

During the first seven days, a fertilised egg becomes a structure called a blastocyst, which contains 200-300 cells.

“The reason why it is so important is because miscarriages and infertility are extremely common, but they’re not very well understood”.

Researchers will look at the earliest stage of human development-the first seven days of a fertilized egg-to gain a better understanding of how a healthy human embryo grows.

Scientists say the technique holds promise for curing diseases like muscular dystrophy and sickle cell anemia, which are controlled by simple genetic defects.

Less than one year after Chinese researchers revealed that they had genetically modified human embryos, scientists at the Francis Crick Institute in London have gotten the go-ahead to conduct similar experiments, officials at the medical research facility revealed on Monday.

UNESCO’s International Bioethics Committee (IBC) said gene therapy could be “a watershed in the history of medicine” and genome editing “is unquestionably one of the most promising undertakings of science for the sake of all humankind”. Kathy Niakan’s investigations into the possible fix and editing of genes found to be of damage-risk in a human embryo.

Dr David King, director of the watchdog group Human Genetics Alert, said: “This research will allow the scientists to refine the techniques for creating GM babies, and numerous Government’s scientific advisers have already decided that they are in favour of allowing that”. Niakan has said in a conference that the first gene she wanted to target was called Oct4.

These embryos will be donated by patients who have given their informed consent to the donation of embryos which are surplus to their IVF (in vitro fertilisation ) treatment, according to the Crick. She believes that this gene may have a decisive role in the earliest stages of human fetal development.

Around the world, laws and guidelines vary widely about what kind of research on embryos that will change the genes of future generations, is allowed. He has served on the National Institutes of Health’s human embryo research panel.

The research, he concluded, “seems to be more about satisfying scientific curiosity about how genes work in the normal development of the human embryo”, pointing to the examples of three-parent embryos and animal-human hybrids as evidence that scientists have made “rash” promised to get approval for controversial treatment.