Gene therapy saves boy’s skin, life

The findings are reported in Nature. Children with the condition have mutations in one of three genes – LAMA3, LAMB3 or LAMC2. “The nice part about working on the skin is that if you develop a cancer, we’ll have the chance to see it more readily because it will be exposed to the surface and we’ll be able to cut it out and remove it before it develops”. And even bumps and bruises healed normally.

In addition to the painful blisters, Rafi needs frequent throat surgeries, because her condition also affects mucous membranes. About 1 in every 20,000 babies in the United States are born with the condition, so roughly 200 children each year. More than 40 percent of those afflicted don’t even survive to adolescence.

By the time his parents brought him into the burn unit at the Children’s Hospital at Ruhr University in Germany in June 2015, the seven-year-old boy was in dire shape.

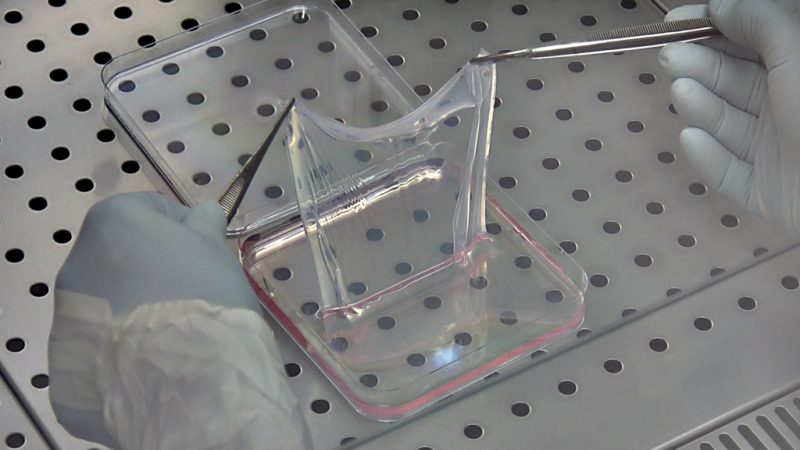

The treatment, outlined in a paper in the journal Nature, involved first taking a sample from the patient’s remaining healthy skin. “We didn’t have any options to treat this child”, says Hirsch.

The experimental gene therapy treatment was developed by Michele De Luca at the Center for Regenerative Medicine at the University of Modena and Reggio Emilia in Modena, Italy. “Now the boy is well, he’s going to school and playing football”, De Luca told ANSA.

Even quite similar trials, though, have not seen comparable rates of insertional mutagenesis, and De Luca said that in skin transplants, “all the preclinical data we have point to a lack of toxicity”, and in clinical work on skin grafts, clinicians have applied “on the order of” 100 million transduced cells, and never observed carcinoma. The researchers needed to replace about 0.85 square meters of skin – 14 times more. The boy’s immune system hasn’t rejected the cells, which are genetically identical to the rest of him, nor did the normal genes insert in ways that could cause cancer.

The basic technique-without the gene therapy-is already used for burn victims. The epidermis contains the cells that form our body’s boundary with the outside world; in epidermolysis bullosa, they lose their ability to hold on to the cells underneath them.

The researchers then corrected the genes in that piece of skin by infecting the cells with a form of virus that contained a fixed version of a faulty gene that causes EB, known as LAMB3. If the gene helps prevent cells from becoming cancerous and dividing uncontrollably, it might actually help cells with this insertion grow in culture. As the skin replenished itself, the holoclones gradually took over, suggesting a small number of stem cells are responsible for growing all the skin. All children can run around and play, why am I not allowed to play soccer? In the months that followed, skin biopsies from the boy showed that his new skin adhered firmly to the underlying dermis, and had normal morphology and levels of laminin b3.

The treatment might be deemed too extreme for many patients and was done on this patient to save his life, but introduced in stages could make life much easier for people with this form of JEB, the researchers write.

His skin no longer blisters or itches, and unlike many burn patients who must apply ointment once or twice a day for the rest of their lives, his repaired skin needs no ongoing treatment. For these errors, correction with a gene-editing tool like CRISPR makes more sense, De Luca says. “He’s not a mouse”.

Put simply, “it’s a attractive piece of work”, stem cell and regenerative medicine researcher Fiona Watt of King’s College London writes to The Scientist about the team’s accomplishment. The team showed that in their work, clusters of one particular type of long-lived stem cell, called a holoclone, were the source of the vast majority of the repeated cycles of regeneration that were undergone by the transplanted skin.

Having a company refocused his team’s attention on a different type of stem-cell therapy, one likely to yield a product for the market faster. They published encouraging results from their first attempt-with small patches of gene-corrected skin on a patient’s legs-in 2006. By the time he came to be treated, he had lost the surface layer of skin, called the epidermis, from nearly his entire body, with only the skin on his head and a patch on his left leg remaining intact.

A seven-year-old child who lost almost all of the outer part of the skin on his body due to a devastating illness, has made a near complete recovery after receiving multiple transplants of a genetically engineered replacement grown in a lab. Over the next 21 months, the regenerated epidermis healed successfully without blistering. “This is a handsome example of how you can move stem cells into the clinic in a very safe and powerful manner”, he says, also calling the work “a powerful demonstration that only a few stem cells are indeed maintaining the skin epidermis rather than many different progenitors”. De Luca said the boy will be monitored closely for skin cancer and other potential issues.