Monkey Brains Wired Together: A Real Life Mind-Meld : Tech : Science World

The brain collectives always did at least as well on those tests as an individual rat would have, and sometimes even better. It has been showed for the first time that a specific behavior could be performed by networking multiple animal brains and harnessing them, said Miguel Nicolelis, a professor of neurobiology and biomedical engineering at Duke University and an expert in brain-machine interfaces.

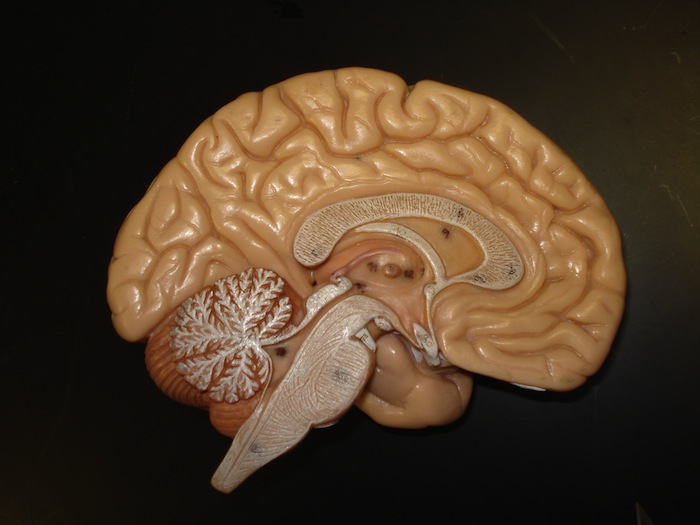

“This is the first demonstration of a shared brain-machine interface, a paradigm that has been translated successfully over the past decades from studies in animals all the way to clinical applications”, said Miguel Nicolelis, M.D., Ph. The study conducted by the neuroscientists at Duke University used brain-machine interfaces (BMI) to investigate the compatibility of brain networks on these animals. In the case of the rat experiment, they then physically linked pairs of rat brains via a “brain-to-brain interface” (see “Rats Communicate Through Brain Chips”).

The researchers tested the ability of rat brain networks to perform basic computing tasks. Once groups of three or four rats were interconnected, the researchers delivered prescribed electrical pulses to individual rats, portions of the group, or the whole group, and recorded the outputs. The brain networks were consistently better than a single brain, especially when the task involved more than one computation step. With time the scientists found that the monkeys were able to increasingly synchronise their actions and coordinate brain activities which led to improved execution of the tasks.

Further, the mind-melded animals learned to synchronize the activity of their neurons and use their combined brain power to carry out tasks involving pattern recognition, storage and retrieval of sensory information and even predicting the chances of rain based on shifts in air temperature and air pressure. The researchers found that the monkeys connected across the B2 brainet were only able to control one of the arm’s movements, up and down, or left and right for example. When the monkeys got the arm to hit the target, the researchers rewarded them with juice. Then they connected two or three of the macaques to a computer with a display showing a CG monkey arm.

Nicolelis says that significant advancements could be made in biomedical science by using the results of the study. For example, he suggests, perhaps neurologically disabled people could share healthy brain activity from others and collaboratively perform virtual reality-based neurorehabilitation training exercises.