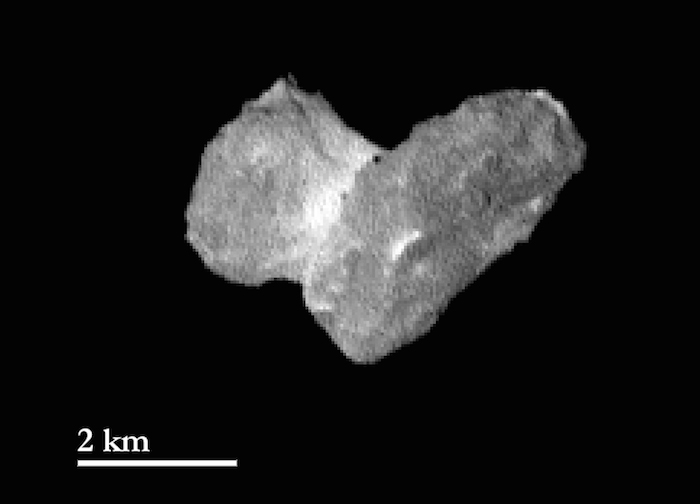

New study reveals how Rosetta’s comet got its ‘rubber ducky’ shape

Comets are valuable assets for scientists studying the early solar system, since they are essentially frozen remains of the same rocks and dust that formed the system’s eight (or nine) planets.

“It is clear from the images that both lobes have an outer envelope of material organized in distinct layers, and we think these extend for several hundred meters below the surface”, study lead author Matteo Massironi, of the University of Padova, Italy, and an associate scientist of the OSIRIS team, said in a news release. But the narrow neck connecting the two lobes has no such features-a sign that the comet didn’t start out as one round, layered object that then gained an unusual shape by spewing material unevenly.

“If you put it together, it looks like you have two onions sitting next to each other, not a single onion with a piece taken out”, he said. In addition, the team looked at gravity vectors that run perpendicular to the strata and found that they matched computer models of two separate objects, rather than a single object.

In essence, this means the comet is made of two separate cores.

The other option is that the so-called “neck region” between 67P’s two lobes experienced some particularly active and still unexplained outgassing over the eons, eroding its more spherical shape into a body that resembles a rubber duck.

Was it the result of a crash, or did the central “neck” linking the comet’s “head” and “body” form through a process of erosion?

In August 2014 Rosetta captured eerie measurements that appeared to show comet 67P/Churyumov-Gerasimenko “singing”.

Professor Massironi added: ‘This points to the layered envelopes in the comet’s head and body forming independently before the two objects merged later.

It is unclear exactly when the two smaller comets collided to form 67P, but it is the latest in a series of discoveries from the comet.

“Comets are also known to carry organic compounds”, he added, “and are thought to be one type of vehicle that delivered water and organic chemicals to Earth – chemicals that could serve as building blocks for more complex molecules underpinning organic life”. “There could have been some processes of cementation during the collision itself and in the following evolution of the comet”.

‘Now, thanks to this detailed study, we can say with certainty that it is a “contact binary”‘.

“They convinced me that these are two things stuck together”, Masiero said.

‘Rosetta will continue to observe the comet for another year, to get the maximum amount of information on this celestial body and its place in the history of our Solar System’.

The knowledge gleaned by the Rosetta photos should help scientists better understand how planets and comets formed, he said.