No jury for Baltimore officer charged in Freddie Gray death

As the pretrial motions began Tuesday in the case of the fourth Baltimore police officer to be charged in the 2015 death of Freddie Gray, at least one thing was glaringly obvious: State’s Attorney Marilyn Mosby (shown, center) doesn’t know when to say when. Next up on the list of officers to be tried is Lt. Brian Rice, the most senior member of the unit deployed on the fateful day when Gray was picked up. The actual trial will begin on Thursday. Both officers who were tried previously opted for bench trials and have now been acquitted. Prosecutors, however, can still cite the agency’s general orders and Rice’s police academy training.

Chief Deputy State’s Attorney Michael Schatzow said the documents had only been obtained last Tuesday after “months and months and months” of seeking them from the city.

People who believe criminal trials are unwarranted in Gray’s death could see this as yet another example of incompetence or bad motives in the prosecutor’s office, he said, while those who believe a crime occurred will likely instead blame the police instead.

City Solicitor George Nilson told The Baltimore Sun after the hearing, however, that prosecutors made an expanded request for Rice’s training documents only on June 18. Schatzow said prosecutors did not want to seek a subpoena.

During the hearing, Judge Williams denied the defense’s motion to drop the charges and the trial will start on Thursday where Rice will face involuntary manslaughter, second-degree assault, two counts of misconduct in office, and reckless endangerment charges. He is now free on $350,000 bail.

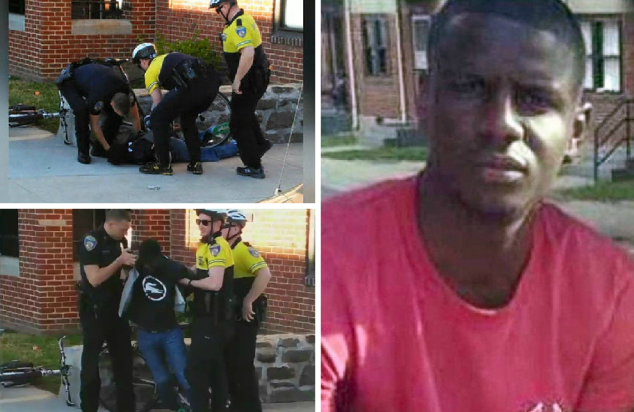

Gray’s neck was broken after cops did not put the shackled Gray, 25, in a seat belt in a metal transport compartment. The most serious charge involves the officer’s failure to secure a handcuffed Gray with a seatbelt in the police van. The first trial in this case was that of Officer William Porter which ended in a mistrial when the jury informed Judge Williams that it would not be able to reach a unanimous verdict.

In 2012, police confiscated Rice’s official and personal firearms after fellow Baltimore police officer Karen McAleer, the mother of Rice’s child, requested a welfare check. Rice helped Nero load Gray into the van. The prosecution alleges that Freddie Gray became hurt due to the officers giving him a “rough ride” and not properly buckling him into the back of the police van. Gray ran once they had “made eye contact” with him, officers said, which caused the young man to run “unprovoked upon noticing police presence.” .

Rice’s trial comes just weeks after the judge acquitted Officer Caesar Goodson Jr., the van’s driver, on all counts, including second-degree depraved-heart murder. The Baltimore Sun previously reported that Detective Dawnyell Taylor said she felt prosecutors presented misleading evidence to grand jurors. Williams admonished the prosecutor for not following the appropriate channels when police did not respond to requests for the documents. They said it took months to get them from the police department, but police now say that’s not true. In another, an attorney alerted the officers’ defense attorneys to a meeting with a witness that had not been disclosed.

But, “it doesn’t mean that was the slam dunk evidence that would be sufficient to prove the evidence beyond a reasonable doubt”, said Jaros. Because prosecutors failed to turn 4,000 pages of documents related to the field training of Lt. Brian Rice, Judge Barry Williams ruled the material inadmissible this morning at a hearing for the 46-year-old officer this morning in circuit court. In a hearing this morning, Assistant State’s Attorney Michael Schatzow told the judge that though prosecutors requested the documents from the police department late previous year, but they did not receive the documents until Tuesday of last week, and only then did they turn over the documents to the defense.

We must weigh the potential financial cost of defending the lawsuits in court and the potential exposure to the citizens of the city of Baltimore if we are unsuccessful in court – and for that matter if we are successful in court.