Scientists May Have Detected Gravitational Waves For The First Time

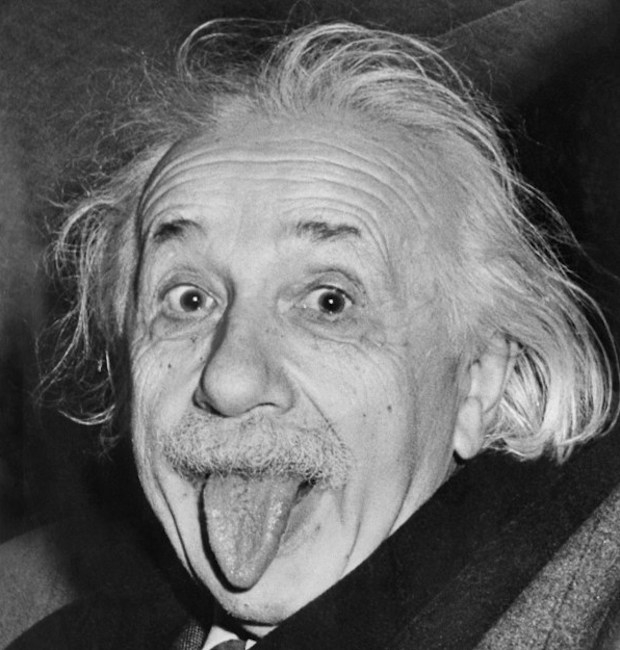

The wave-making rumor focuses on the possibility that the Laser Interferometer Gravitational-Wave Observatory (LIGO), which is operated by the California Institute of Technology and the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, has discovered gravitational waves. They were first predicted a century ago by Albert Einstein in his general theory of relativity.

The discovery would open a new window on the universe by showing scientists for the first time that gravitational waves exist, in places such as the edge of black holes at the beginning of time, filling in a major gap in our understanding of how the universe was born.

According to the rumors, scientists on the team are in the process of writing up a paper that describes a gravitational wave signal.

Whispers of a possible detection were first tweeted in September by cosmologist Lawrence Krauss, at Arizona State University in Tempe.

“We take pride in reviewing our results carefully before submitting them for publication – and for important results, we plan to ask for our papers to be peer-reviewed before we announce the results – that takes time too!”

The physics community is unable to contain its excitement, after news about direct discovery of gravitational waves, reported Gizmodo.

Now Krauss claims that the original rumour has been confirmed by an independent source.

“If general relativity is correct, there is no wiggle room in what the signal looks like”, says Pretorius, who in 2005 became the first physicist to complete a full computer simulation of a black-hole merger, which provided a detailed prediction of the shape and size of the gravitational waves that it would unleash.

LIGO wasn’t successful during its search for gravitational waves between 2002 and 2010. Although there is indirect evidence of gravitational waves carrying away energy from orbiting bodies (through extended observations of binary pulsar and white dwarf systems), the detection of the extremely slight impact of the propagation of gravitational waves that are hypothetically washing though our planet has been maddeningly hard to achieve. The most specific rumour now comes in a blog post by theoretical physicist Luboš Motl: it’s speculated that the two detectors, which began to collect data again last September after a $200-million upgrade, have picked up waves produced by two black holes in the act of merging. The instrument splits a laser beam into two, and sends one beam in a perpendicular direction while the other continues along its originally track.

This is why the distance between each LIGO detector is over 1800 miles, because that’s about how long LIGO scientists think the gravitational waves they’re searching for should be.

LIGO scientists are keeping mum. When the beams reflected off the mirror, the two beams should return at the same time, since they’re both traveling at the speed of light.

Therefore, if one detector observes a gravitational wave, it should mean the other detector should measure the same signal, offering immediate confirmation that the observation at the first detector isn’t a fluke.

But if they do succeed, it will revolutionize astronomy as we know it.